The Monument Complex of Thornborough, North Yorkshire

Twelve kilometres north of Ripon is Britain’s best kept prehistoric secret — the three giant Thornborough henges, circular ritual earthworks each about 240m across. They represent one of the largest earthmoving episodes undertaken in Neolithic Britain and are at the heart of a remarkable ‘sacred landscape’ in use for over 2,000 years.

The earlier and middle Neolithic (3800-3000 BC)

People may have first been drawn to Thornborough by the River Ure, a route between the Pennines to the west and Yorkshire’s low-lying vales to the east. This is no modest watercourse, but a powerful natural symbol, and a possible focus for local religious belief.

Perhaps this is why the earliest known monument, a triple-ditched round barrow, was found nearby. Excavation has revealed a small oval-shaped inner pit and within it a hand bone and skull fragment. The pit had been cut by another into which were placed the remains of at least 3 adults and 1 juvenile. Selected bones had been selected for deposition here, suggesting that the bodies were left elsewhere to decay. The site developed between 3800-3500 BC, with the digging of three encircling ditches and the construction of a large imposing circular mound of soil and cobbles.

This ‘founder monument’ was superseded in the latter half of the fourth millennium BC by the building of a rectilinear ditched and banked enclosure, or cursus, at least 1.1 km long and around 44 m wide. It ran along the highest part of the terrace, its rounded western terminal aligned on a major bend in the river. These enigmatic monuments, well known from river valleys elsewhere, may have been ceremonial procession-ways possibly associated with the dead. Near its eastern end was a small oval enclosure, originally with an inner bank and broken by a number of entrances. Its date and role remain a mystery, but the site’s layout is typical of so-called ‘long mortuary enclosures’, seen by some as places where the dead were left to decay before the bone’s deposition in other monuments.

Worked flint from the ploughsoil demonstrates the exploitation of the wider landscape. Much of the activity was taking place on the lower slopes of the gravel terrace, nearest the River Ure, or higher on and around the terrace, often across very slight ridges. Locally available flint and chert was well-used and a number of earlier Neolithic scatters were the product of everyday knapping at small, and most likely, temporarily occupied camps.

The later Neolithic (3000-2200 BC)

The earlier Neolithic complex was superseded by the far grander three henges. These very similar and equally-spaced earthworks, all with the same north-west/south-east alignment, were built on the plateau, the central site deliberately located over the earlier cursus. To have three like this is completely unique and is all the more impressive when we consider their scale and complexity. They demonstrate a massive commitment of labour and an impressive degree of planning.

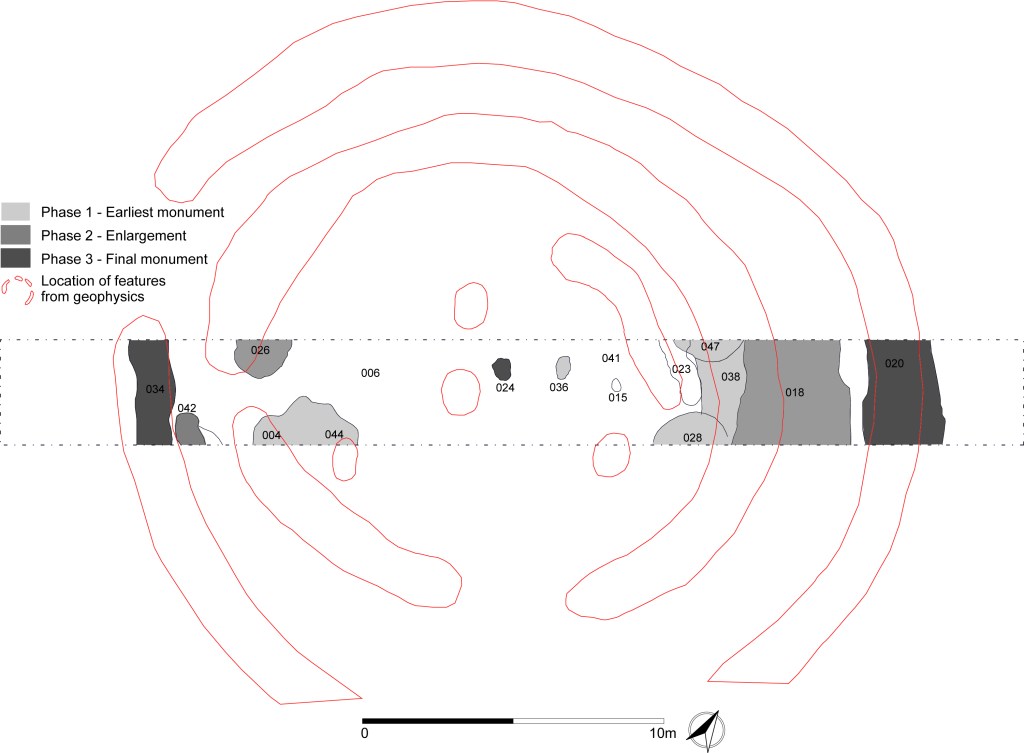

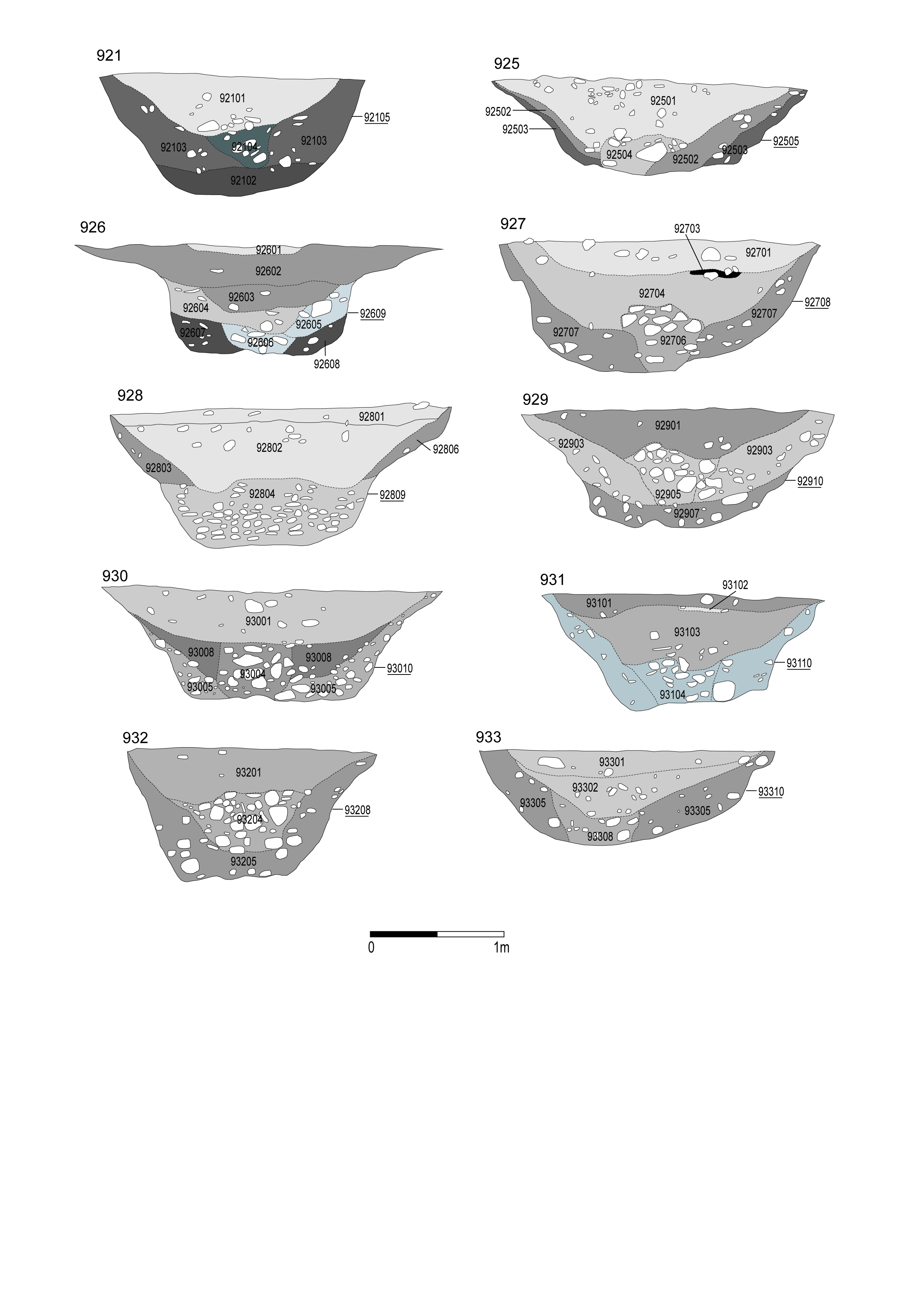

Their outer ditches are discontinuous and interrupted by as many as five entrances, in contrast to the massive and more continuous inner earthworks that separate an inner arena from the outside world. Excavations demonstrate that the ditches would have been 15m wide and about 3m deep, while the banks are as much as 18 m across, and originally coated in gypsum, making them a striking white colour. Other known features include the remains of a banked entrance structure and stake-holes in the northern entrance of the southern henge, and some unexplored geophysical anomalies from their interiors, including a large flattened ‘V’-shape across the centre of the southern henge. Further investigation would likely add to the impression that these were complex and impressive monuments.

In contrast to earlier times, the plateau was kept clear of everyday occupation as people undertook celebrations and commemorations. There was a sharp decline in the amount of worked flint and chert in the immediate vicinity of the henges. This was more than matched by finds typically over 600m away, especially on a low till knoll known as Chapel Hill, some 900m east of the central henge. These patterns suggest a landscape with zones of different meanings, with the small, temporary camps of those visiting the complex located towards the terrace edge and across the ridges which surround the plateau.

But why did this landscape become so important? Henges are often close to rivers, indicating their links with communication and movement. The case is especially well made for Thornborough, for its three henges, along with another three downriver at Nunwick, Hutton Moor, and Cana Barn, could mark the location of what has been called the ‘Great North Route’ running north to south, and connecting with a number of trans-Pennine routes. It is even possible that the area attracted pilgrims, who, like their historical counterparts, travelled to seek spiritual guidance and salvation. These three other henges are all very similar in their size and design to those at Thornborough.

The Bronze Age (2200-800 BC)

The ‘sacred landscape’ continued to change. It is not yet possible to say when the henges went out of use, but in the earlier Bronze Age at least ten round barrows were built close by, including the Three Hills cemetery, which originally consisted of four or more burial sites. Some were even located on the axis of the earlier enclosures, as with the barrow between the central and southern henges. Little is known about these monuments, but the four excavated by the Reverend W.C. Lukis in 1864 produced urned cremations and the remains of a coffin. Other additions in the 2nd millennium BC included the construction of a massive double timber avenue near the southern henge, connecting together two round barrows. Along its 350m length are 90 sub-circular pits, varying greatly in their diameter and depth. Post ‘voids’, ‘pipes’ and stone packing show that many once held substantial timber uprights.

Thornborough then became an agricultural landscape. We can see this important change at the Nosterfield Quarry, immediately to the north of the monument complex, where what appears to be a Bronze Age field system was discovered, with ditches up to 4m wide and 1.5m deep, along with single pit alignments. This is not to say that Thornborough was no longer a place of ceremony, for three ring ditches, one of which is definitely the ploughed-out remains of a round barrow, and a number of cremations and inhumations burials — some placed deliberately in the pit alignments — were found amongst the fields. Those farming clearly felt the need to bury their dead nearby.

Copyright of all of the above illustrations is held by Dr. Jan Harding and by the Council for British Archaeology

A detailed account of Thornborough’s archaeology can be downloaded for free at https://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/library/browse/issue.xhtml?recordId=1181583’.

Further information can also be found at https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/places/thornborough-henges/history/

Designed with WordPress